Wedding of the Waters: The Erie Canal and the Making of a Great Nation by Peter L. Bernstein

When the Erie Canal opened in 1825, it was the marvel of its age. Stretching from Buffalo on Lake Erie in the west to where Albany meets the Hudson in the east, the canal had an immediate impact upon opening for travel. Goods were transported at one-tenth the previous cost in less than half the time. It carried over 33,000 commercial shipments at its peak and fostered an explosion of population growth in the west. It transformed New York into the Empire State and catapulted New York City with its deep-water harbor into America’s commercial capital. Its impact was so dramatic it is still felt today as 80 percent of the population of upstate New York still lives within 25 miles of the route of the Canal.

Despite this dramatic impact, the canal was contested and in some quarters, vehemently opposed both during its planning and during its construction. In fact, without the tireless support of U.S. Senator and ten time mayor of New York City, DeWitt Clinton throughout, it surely would not have been built.

Peter Bernstein’s captivating account of this project details a brief history of canal-building around the world, as well as the domestic political squabbles, financing, engineering miracles and Yankee ingenuity that, impossibly, saw the canal built in a mere 8 years. This despite the absence of any sort of modern construction technology. In fact, Bernstein’s descriptions of the resourceful ways in which the workers cleared virgin forests and tackled complex engineering challenges are some of the most fascinating moments of the book.

“It certainly strikes the beholder with astonishment, to perceive what vast difficulties can be overcome by the pigmy arms of little mortal man, aided by science and directed by superior skill. ”

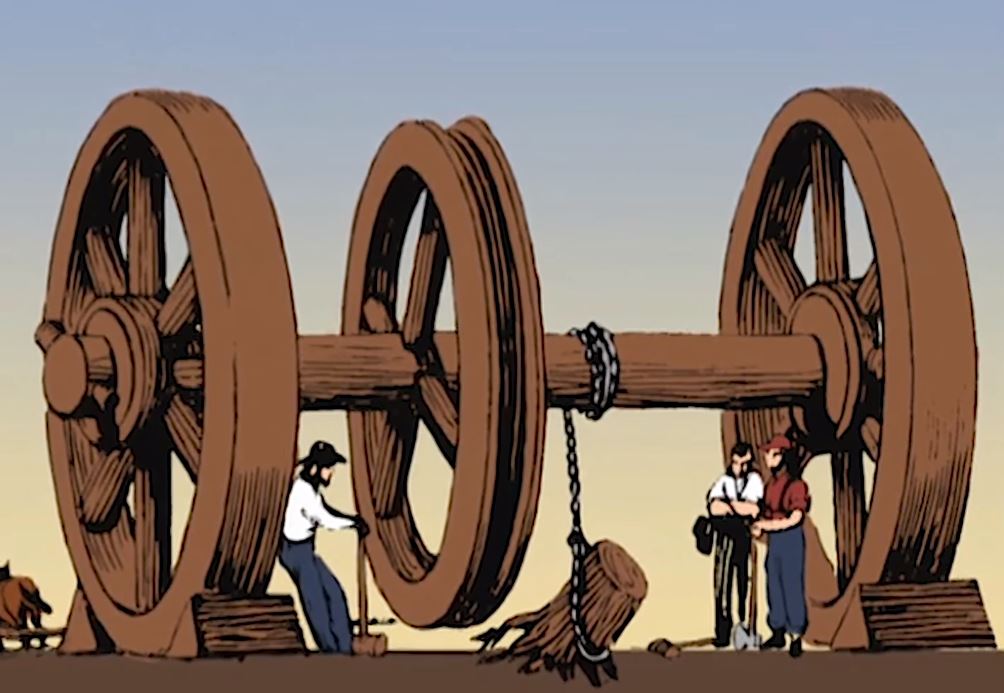

Take for instance the manner in which trees were cleared in the dense forests that the canal route cut through. They began by throwing a rope over the top branches of the tree and pulling it down to earth. Of course, then they were left with a stubborn, broken stump. These were extracted by a device which consisted of two massive wheels that were mounted loose on the ends of an axle. A third wheel, a bit smaller than the others, was fixed to the center of the axle. They then wrapped a massive chain around the axle which was then hooked to the stump. A rope was wrapped around the center wheel and hooked to a team of horses or oxen, which then walked forward. Pulling the chain and ripping the stumps out of the soil. The workers proceeded in this manner, mile by mile, year after year using mostly teams of locals as they passed through the vast countryside of upstate New York. They were paid $10 a month, and apparently casks of whisky were placed along the canal route as a means of encouragement.

They built massive stone aqueducts that carried the canal across rivers and valleys and constructed 83 locks in order to navigate the hundreds of feet of elevation change between Albany and Buffalo.

Though one could no doubt fill a book with these tales alone, Bernstein doesn’t begin to describe the actual construction of the canal until nearly 200 pages in. For the story of the Erie Canal is also the story of an immense political effort as the canal’s advocates had to persistently prove its worth and fiscal viability (the canal paid for its $7 million cost within only 9 years of opening.)

If I had one quibble with the book, it would be the lack of illustrations. There is so much talk of routes and rivers, crossings and construction sites, not to mention the complex feats of engineering, it is sometimes hard to get a clear picture of what is being described and the book suffers a bit from want of pictorial explanation.

The story of the Erie Canal is the story of one of the most inspiring public works projects in American history. While considered the most amazing engineering feat of its time, it was completed, for the most part, by people without any formal engineering training or expertise. The building of the canal is America at its best, and Bernstein takes us all along for an exhilarating ride. “Low bridge, everybody down!”