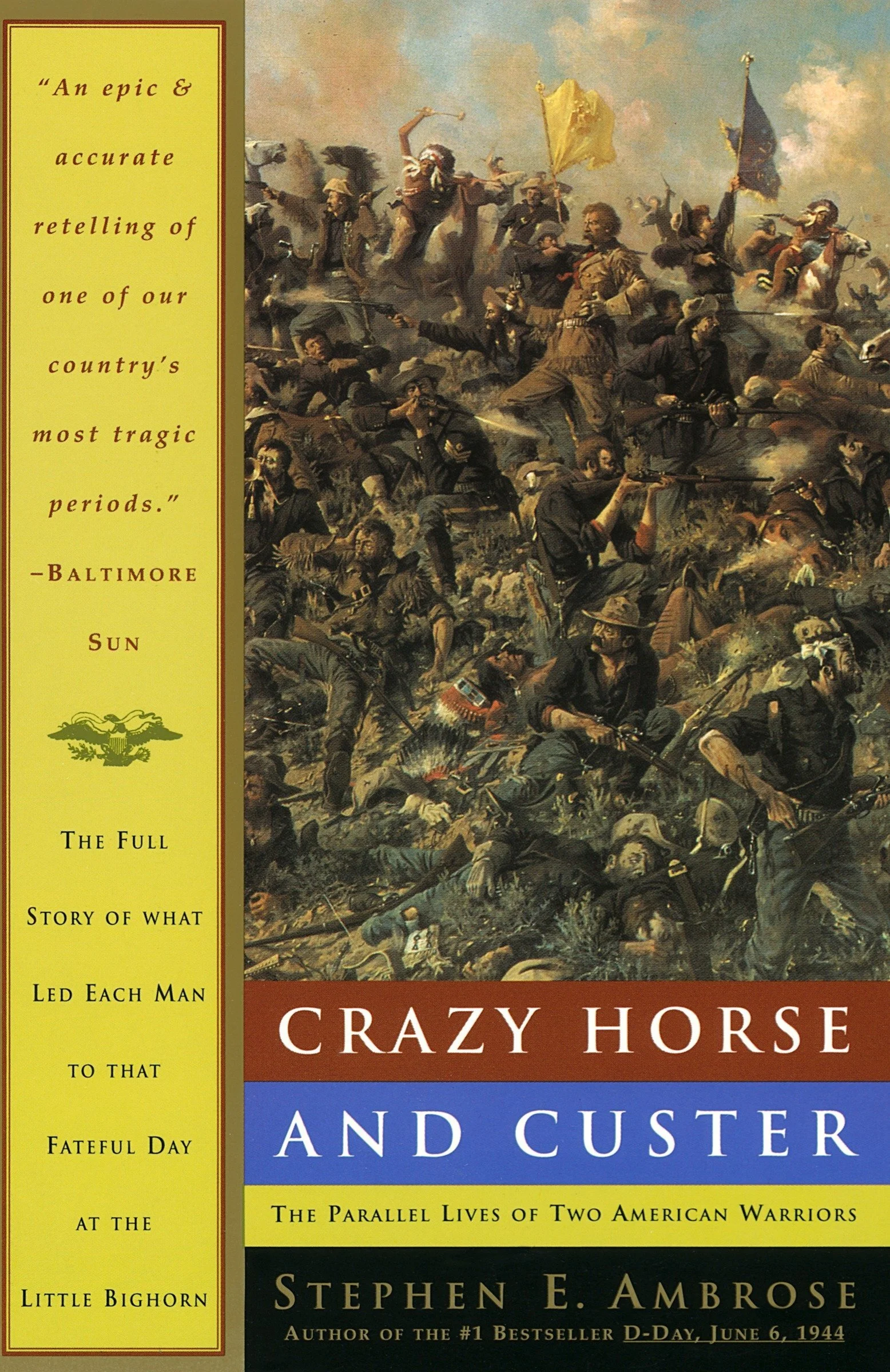

Crazy Horse and Custer by Stephen Ambrose

Philbrick’s Last Stand left me wanting more. I wanted to learn more about Crazy Horse and I felt there was more to know about Custer as well. I had picked up Ambrose’s Crazy Horse and Custer a year or so ago and when I went browsing my bookshelves for more on the period, Ambrose’s book jumped out as the perfect compliment.

I was also getting ready to leave on a trip to the Dakotas and the Black Hills specifically, so another book on these men would offer some great research for my trip.

All that being said, Ambrose’s Nothing Like It in the World left me a little cold, so I was a bit hesitant to pick up another Stephen Ambrose book so soon after the last one. I decided I would read the introduction and then make a decision to read the rest of the book or move on in my journey.

I read the introduction, then the first chapter, then the next, and before I even remembered I was just perusing it on a trial basis, I was well into the story and hooked.

This is a true dual biography. The first half of the book is a bit more weighted towards Crazy Horse, while the second half follows Custer a little closer. At 500+ pages though, I didn’t feel either man got short shrift.

Throughout, Ambrose did a fine job weaving the lives of these two very different and yet in some ways very similar men into an engrossing narrative that also served as a broad history of the era.

Indeed, both men were military leaders: Crazy Horse, leader of the Oglala Lakota, and General George Armstrong Custer of the Seventh Cavalry. Both demonstrated celebrated courage on the battlefield and became leaders at a very young age. Both also had to work through periods of controversy, well-detailed throughout.

Though the book’s climax deals heavily with the years leading up to and just after the Great Sioux War of 1876, we’re treated to a great deal of contextual history as well throughout the young men’s boyhoods and teenage years.

I came away learning a lot about Lakota Sioux culture. Ambrose goes into great detail on how Indian visions shaped their views of themselves and their role in society. I learned about the Sun Dance rituals in which men like Sitting Bull would undergo self-torture in honor of the Great Spirit or Wakan Tanka and how touching your enemy in battle, or Counting Coup, shaped not only the Lakota honor system but also influenced their battle tactics.

I was also fascinated to learn more about homosexual Native Americans during this period, known as ‘winktes’, and was pleasantly surprised to see Ambrose devote ample time to a couple of winkte Lakota men throughout the narrative. This book was written in 1975, not a period particularly known for popular studies of homosexuals, at least in this genre of narrative history. We first encounter Pretty One, a childhood friend of Crazy Horse.

Pretty One was Curly’s childhood friend and later played a crucial role in his career, but by the time he was ten Pretty One wore paint and quilled buckskin and beads every day. He did not enjoy the rough boys’ games that Curly reveled in. Pretty One was well on his way to becoming a winkte, or homosexual, a man who dressed in fancy clothes, sometimes even wearing a dress, did bead and quill work as well as a woman and often became a shaman. The winkte was recognized as wakan, or holy; a Sioux woman told Royal Hassrick that “there is a belief that if a winkte is asked to name a child, the child will grow up without sickness.”

Indeed, the Lakota seemed to have a fairly progressive view of winktes considering the predominance of their warrior culture and the times they lived in.

Even the bravest warriors sometimes slept with a winkte, although the general attitude toward homosexuality was negative. There was obvious ambivalence; the winkte was held in awesome respect on the one hand and in disdainful fear on the other. Curly and his friends sometimes teased Pretty One, but usually ignored him. The important thing was that no one questioned his choice, for his life role had been revealed to him in a dream, and no Sioux would ever consider arguing with someone’s dream.

Of course, there was a great deal to be learned about Custer’s United States as well.

Ambrose, never afraid to offer modern equivalents in his works if it helps the reader understand his subject better, delivers some insightful thinking regarding the strategies and limitations of the opposing aggressors, in this case, the Indian tribes and the U.S. Army.

The truth was that fighting Indians on the Plains was more like naval warfare on the high seas than anything else. In effect, Sherman was lumbering around with battleships and cruisers, chasing pirates in sleek, much faster vessels. Worse, his ships had no staying power; they had to put into port (the forts) every other week or so to replenish their supplies. The pirates could live off the ocean. To continue the image, the wagons were merchant vessels. When they traveled alone, as did the stagecoaches, the pirates gobbled up every one they saw. When the wagons traveled in convoy, protected by fighting men, they got through.

And though Ambrose demonstrates real empathy for the plight of these tribes throughout the text, he’s also very much a realist. For instance, he offers this summation of the U.S. government’s pattern of behavior:

From the time of the first landings at Jamestown, the game went something like this: you push them, you shove them, you ruin their hunting grounds, you demand more of their territory, until finally they strike back, often without an immediate provocation so that you can say “they started it.” Then you send in the Army to beat a few of them down as an example to the rest. It was regrettable that blood had to be shed, but what could you do with a bunch of savages?

But then also, a few paragraphs later, compliments it with this:

Well, it was regrettable, but who is to say they were wrong? Who can possibly judge? Who would be willing to tell the European immigrant that he can’t go to the Montana mines or to the Kansas prairie because the Indians need the land, so he had best go back to Prague or Dublin? Who wants to tell a hungry world that the United States cannot export wheat because the Cheyennes hold half of Kansas, the Sioux hold the Dakotas, and so on? Despite the hundreds of books by Indian lovers denouncing the government and making whites ashamed of their ancestors, and despite the equally prolific literary effort on the part of the defenders of the Army, here if anywhere is a case where it is impossible to tell right from wrong.

No doubt many modern readers would take issue with this stance, so eager are we these days to do just that: declare right and wrong. But Ambrose is not wrong in the broad sense that these actions (discovery, conquest, subjugation, assimilation) have been historical through lines across cultures, eras, and peoples since time immemorial. Indeed even the Native tribes themselves practiced these very actions amongst themselves, constantly making war on other tribes for land, material goods (mainly ponies), and pride.

This isn’t so much a defense of the actions of the U.S. during this period. It’s just to say - this is what people do to each other. It’s brutal and ugly and violent. This is our past. This is us. All of us. We can only hope that we’re evolving and that the arc of history will bend towards future justice but history has shown us that we will continue to find unique ways to brutalize each other.

Crazy Horse and Custer is a remarkable book. I’d put it right alongside Undaunted Courage as one of Ambrose’s best. Even today, in my visits to the book shops at the Crazy Horse Memorial and Theodore Roosevelt National Park I came across brand new modern editions of this 45-year-old work alongside other more recent efforts, evidence that it’s still held in high regard. In my mind, its spot on the shelves is well-earned.